Will This Excellent New Signal Messenger Update Make WhatsApp Users Switch? - Forbes

Will This Excellent New Signal Messenger Update Make WhatsApp Users Switch? - Forbes |

- Will This Excellent New Signal Messenger Update Make WhatsApp Users Switch? - Forbes

- Zoom Finally Has End-to-End Encryption. Here's How to Use It - WIRED

- [Update: Apple explains and addresses] Recent server outage reveals potential Mac privacy concerns - 9to5Mac

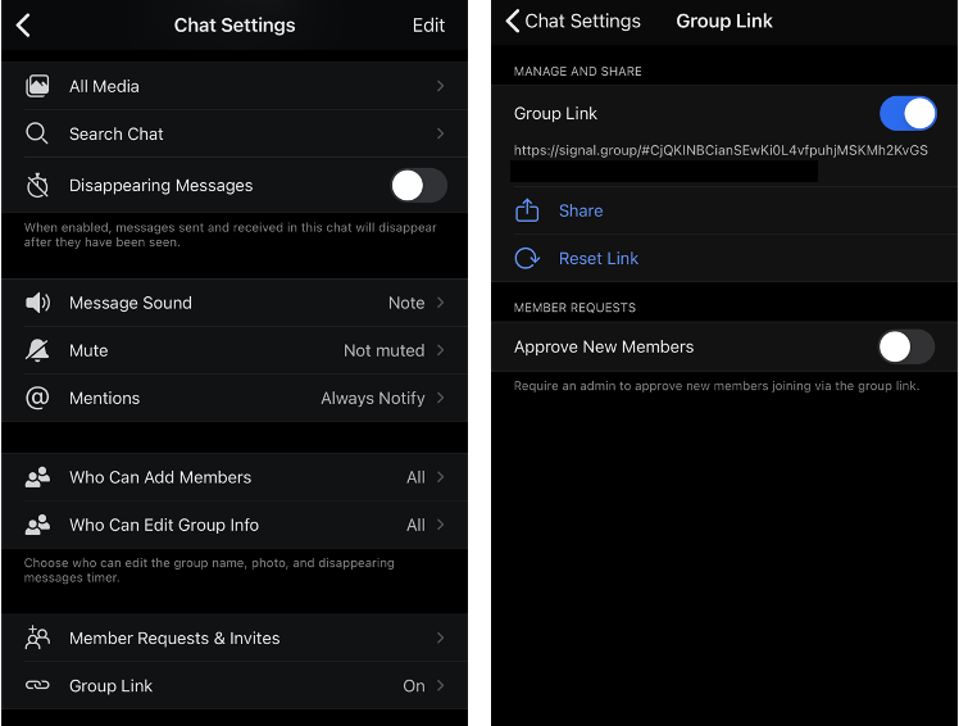

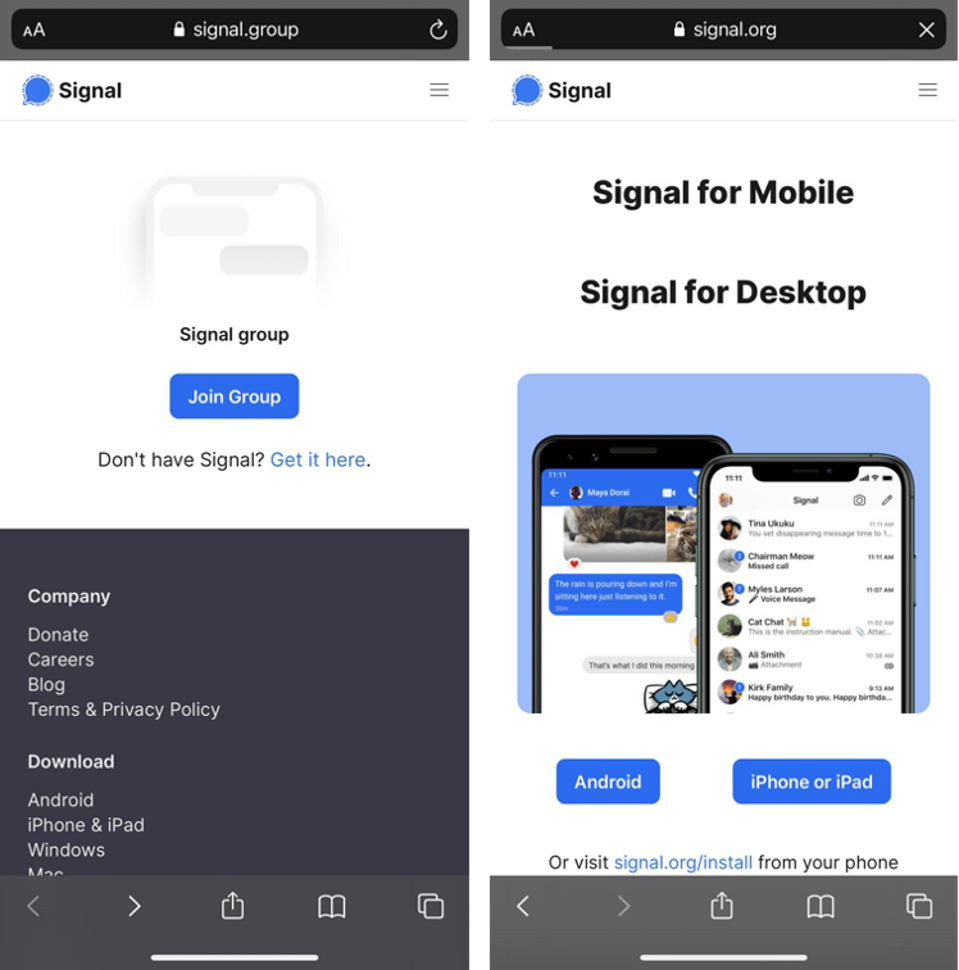

| Will This Excellent New Signal Messenger Update Make WhatsApp Users Switch? - Forbes Posted: 01 Nov 2020 12:00 AM PDT  Getty Despite its continued dominance of the secure messaging space, now delivering some 100 billion messages each day, WhatsApp is coming under more pressure than ever before. Until recently, it was the only secure messenger that would work cross-platform and that would likely appeal to all your friends and contacts. But as the messaging wars continue to heat up, rivals sense an opportunity to solicit WhatsApp users. WhatsApp has one major advantage over these rivals—the sheer scale of its install base. With two billion users, you can almost guarantee your contacts have the app. And that makes it the only secure platform that's a genuine SMS alternative. Telegram remains surprisingly outside the mainstream, given its 400 million users. iMessage cannot extend outside Apple's ecosystem without reverting to unsecured SMS. All the others are too small—for now. But WhatsApp also has two huge disadvantages. First, its missing functionality—no option to access messages from multiple devices, the desktop scrape from your phone doesn't count, and no secure backup option which means no secure means to move your chat history to new phone. And, second, the biggie—WhatsApp is owned by Facebook, which is even now beginning to properly monetize the platform. And, like it not, there's a sizable percentage of that 2 billion strong userbase that simply doesn't trust Facebook. And this will be made worse as news continues to leak out about the integration of Facebook's commercial machine and your WhatsApp messages. Putting all that together, there's an opportunity to steal users from WhatsApp, if you're not tainted by Facebook ownership, if you can plug the functionality gaps, and if—the big if—you can build a critical mass of users to make yourself a viable alternative. WhatsApp's upstart and uber-secure rival Signal—once too specialist to threaten the bigger players, already has better critical functionality: multiple device access and secure device upgrades. But it's small—and that means WhatsApp users can't be sure their contacts will have the app installed. Well now Signal has hatched a brilliant plan to resolve this. And it could be a game-changer. MORE FOR YOU  Signal/iOS Signal already notifies users when contacts on their phones sign up—it's intended as a viral prompt to switch chats with those contacts to Signal, although it horrifies the privacy-first brigade. Signal's newly hatched plan is much smarter than this. Its users can now set up a new group, one with no members, and then create a "group link," which can be sent to your contacts. When they click the link, they'll automatically join the group. If they don't have the app, they'll see a link to install it on their devices.  Signal/iOS As Signal points out, "you can easily share group links to another Signal chat or to other apps." Let's be very clear. Their intention is for you to send the link in a WhatsApp group to shift it wholesale to Signal. Anyone who's been using WhatsApp for some time will have a wide range of groups, some you use and some you don't. Shifting the ones that you use most regularly to this non-Facebook platform could easily catch-on. Signal is rapidly improving its group functionality and this new move now makes it easier to set up new groups on Signal than on WhatsApp: "Group links make it easy to get people into your group without having to add them 1-by-1. If you're trying to organize an event, for example, simply share your group's link on Twitter or with another Signal chat to quickly get interested people in the group. If you want to move a group chat from another service to Signal, sharing a group link can simplify that." Signal groups are much more private and secure than those on WhatsApp—there's no contest. Signal's announcement points to when it confirms that "the Signal service has no access to your group memberships, titles, avatars, or attributes, the Signal service can't access your group links. The information needed to join the group is embedded in the link itself and only a group's members can access the link, not Signal." It's the capturing of this type of metadata centrally that has been a criticism of WhatsApp—it's unclear what it monitors and captures, but it is clear that while message content is end-to-end encrypted, all of the metadata around who you know and who you message, and when, plus your groups and when you access the service can be monitored. It's also clear that the recently confirmed plans to further commercialize WhatsApp risks making that worse. And for many this will be the crux, the reason they move from WhatsApp to a messenger that actually focuses on securing their communications rather than commercializing their usage. With the latest news that WhatsApp's new, paying business customers can manage your WhatsApp chats with them on Facebook's backend, where those chats will fuel marketing efforts, will be poorly received. By contrast, Signal famously doesn't even store basic metadata—the platform boasts that it can't fulfil law enforcement requests for data it doesn't have. This made it the messenger of choice for protesters this year across the U.S. and in Hong Kong and elsewhere. Earlier this month, Signal launched desktop voice and video calls. We have known for some time that WhatsApp has this in the works—those plans appeared to accelerate in light of Signal's launch. It's hardly a surprise that WhatsApp monitors Signal's initiatives. WhatsApp co-founder Brian Acton is a major backer of the non-profit foundation behind Signal. And it's a tweaked version of Signal's encryption protocol that protects your WhatsApp content. Signal has tens of millions of users—bit its installs are soaring. It is easy and intuitive to use. In fact, the only drawback is that it doesn't offer a cloud backup option—security wins out on that one. If you lose your phone, you lose your messages. But given that WhatsApp's backup option invalidates the end-to-end encryption used to protect your content, you can see why that's not such a sacrifice. Once WhatsApp fixes this—yet another development in apparently in the works, then the equation may change. For now, WhatsApp still remains the best go-to messenger. But the situation is changing rapidly. Most security professionals recommend Signal over the alternatives, and with good reason. This is yet another prompt for you to install the app and try it for yourself. Move one of your groups across and see what you think. |

| Zoom Finally Has End-to-End Encryption. Here's How to Use It - WIRED Posted: 02 Nov 2020 12:00 AM PST  Zoom has gone from startup to verb in record time, by now the de facto video call service for work-from-home meetings and cross-country happy hours alike. But while there was already plenty you could do to keep your Zoom sessions private and secure, the startup has until now lacked the most important ingredient in a truly safe online interaction: end-to-end encryption. Here's how to use it, now that you can, and why in many cases you may not actually want to. It's been a long road to get here. This spring, as Zoom rode the pandemic to video call ubiquity, close observers noticed that the company was calling a feature "end-to-end encrypted" when in fact it was not. Data could be encrypted, yes, but lacked the critical "end-to-end" part, which means that no one—not Zoom, not hackers, not government snoops—can access it as it travels from one user to the other. It's the difference between your landlord keeping a key to your apartment and being able to change the locks yourself: not the end of the world in either case, but you'd want to know for sure. Especially if you don't trust your landlord. You likely already use end-to-end encryption in some form or another. It's on by default for iMessage and WhatsApp, a staple of encrypted messaging platforms like Signal, and an optional feature in Facebook Messenger. For video chat, your options are more sparse. Apple offers it for up to 32 participants on FaceTime, while WhatsApp allows up to eight people at a time. Signal can manage only one-on-one encrypted calls at the moment. Suffice to say, it's a hard thing to get right. And so Zoom went on a spending spree, bringing on high-profile consultants from the world of cryptography and buying up Keybase, a company that specializes in end-to-end encryption. The result of that flurry: Zoom finally delivered on its security promises at the end of October. What Zoom launched is actually a 30-day technical preview; the company will continue to refine the offering through next year. But even in its early days, it offers a significant upgrade in protection for those who need it most. A Few Limitations There are a few caveats before deciding whether you want to fully end-to-end encrypt your Zoom calls. First is that Zoom meetings are encrypted by default regardless, just not end-to-end. Which is to say, they're likely safe enough for most people most of the time. You should absolutely flip the switch for sensitive conversations, but otherwise, as you'll see in a minute, it may be more trouble than it's worth in a lot of instances. Also remember that encryption isn't magic; the people that you're talking to could still share whatever you say. And if any of your devices are compromised, well, you're out of luck. Turning on end-to-end encryption comes with various inconveniences. When you have it enabled, all call participants need to call in from either the Zoom desktop or mobile apps—not a browser—or a Zoom Room. (That also means no telephone participants.) Features like cloud recording, live transcription, breakout rooms, polling, one-on-one chat, and meeting reactions aren't compatible with end-to-end encryption, and no one can join the meeting before the host does. You also need a Zoom account to enable it, which, fair enough. But while Zoom has relented on its previous stipulation that only paying customers could access end-to-end encryption, free accounts still need a valid phone number and billing option to take advantage, which Zoom has said helps prevent abuse of the feature. Turn on End-to-End Encryption So! With all of that out of the way, here's how to actually use Zoom's end-to-end encryption, if it's right for you. It's a little different depending on whether you're doing so for yourself, for a group, or for all the users in an account that you administer. The good news is, the directions are the same regardless of whether you're on iOS, Android, or the desktop client. |

| Posted: 15 Nov 2020 12:00 AM PST As Apple launched its new macOS operating system to the public yesterday, serious server outages occurred that saw widespread Big Sur download/install failures, iMessage and Apple Pay go down but more than that, even performance issues for users running macOS Catalina and earlier. We learned why that happened at a high-level yesterday, now security researcher Jeffry Paul has shared a deep-dive of his understanding along with his privacy and security concerns for Macs, especially Apple Silicon ones. Update: Apple has shared a response to Paul's concerns in an updated support document that includes what macOS does to protect your privacy and security, and three new steps it will take in the future for greater privacy and flexibility.

Update 11/15 8:25 pm PT: Apple has updated a Mac security and privacy support document today sharing details about Gatekeeper and the OCSP process. Importantly, Apple highlights it doesn't mix data from the process of checking apps for malware with any information about Apple users and doesn't use the app notarization process to know what apps users are running. The company also details Apple IDs and device identification have never been involved with these software security checks. But going forward "over the next year," Apple will be making some changes to offer more security and flexibility for Macs. First is that Apple will stop logging IP addresses during the process of checking app notarizations. Second, it's putting in place new protections to prevent server failure issues. And finally, addressing the overarching concern that Jeffry Paul raised, Apple will release an update to allow users to opt-out of using these macOS security protections.

We've also learned more technical details about how this all works from Apple that aligns with what independent security researcher Jacopo Jannone shared earlier. macOS' process of using OCSP is a very important security measure to prevent malicious software from running on Macs. It checks to see if a Developer ID certificate used by an app has been revoked due to software being compromised or events like a dev certificate being used to sign malicious software. Online certificate status protocol (OCSP) is used industry-wide and the reason why it works over unencrypted HTTP connections is that it is used to check more than just software certificates, like web connection encryption certificates. If HTTPS were used, it would create an endless loop. Jannone explained it succinctly: "If you used HTTPS for checking a certificate with OCSP then you would need to also check the certificate for the HTTPS connection using OCSP. That would imply opening another HTTPS connection and so on." Two notable points on this are that it's not strange for macOS to be using unencrypted requests for this as that's the industry standard and that with Apple's commitment to security and privacy, it is investing in creating a new, encrypted protocol that goes above and beyond OCSP. In addition to the OCSP process currently used by Apple, macOS Catalina and later also have another process where all apps are notarized by Apple after having checked for malware. When launching an app, macOS makes another check to make certain the app hasn't become malicious since the first notarization. This process is encrypted, isn't usually impacted by server issues, and indeed wasn't affected by the OCSP issue. As for the performance problems we saw on macOS Catalina and earlier during Apple's server issues last week, they were caused by a server-side misconfiguration that was exacerbated by an unrelated CDN misconfiguration. Those issues were resolved on Apple's end a few hours after they began with no action needed to be done on the users' part. Between the explanation of how everything is working here and the commitment to the future changes described above, Apple shows it is listening to users and putting privacy and security first. Update 11/15 9:00 am PT: More details about Apple's use of OCSP have been shared by cybersecurity researcher Jacopo Jannone. He says that macOS isn't sending a hash of each app to Apple when they run and explains why the industry-standard OCSP doesn't use encryption. Further, he says Paul's analysis "isn't quite accurate" and importantly notes that Apple uses this process to check and prevent apps with malware from running on your Mac. Read more from Jannone here. Original post: Not long after macOS Big Sur officially launched for all users, we started seeing reports of extremely slow download times, download failures, and in the cases that the download did go through, an error at the end that prevented installation. At the same time, we saw Apple's Developer website go down, followed by outages for iMessage, Apple Maps, Apple Pay, Apple Card, and some Developer services. Then the reports flooded in about third-party apps on Macs running Catalina and earlier not launching or hanging and other sluggish performance. Developer Jeff Johnson was one of the first to point out what was going on: an issue with Macs connecting to an Apple server: OCSP. Then developer Panic elaborated that it had to do with Apple's Gatekeeper feature checking for app validity. Now security researcher and hacker Jeffry Paul has published an in-depth look at what he saw happen and his related privacy and security concerns in his post "Your Computer Isn't Yours."

He goes on to explain what Apple sees from the process:

Paul continues by posing the argument many readers might be thinking: "Who cares?" He answers that by explaining that OCSP requests are unencrypted and it's not just Apple who has access to the data:

Paul mentions some workarounds to prevent this tracking but highlights that those may be gone with macOS Big Sur.

Paul highlights that Apple's new M1-powered Macs won't run anything earlier than macOS Big Sur and says it's a choice:

He updated the post to share that there may be a workaround via the bputil tool but that he'll need to test it to confirm that. In closing, Paul says "your computer now serves a remote master, who has decided that they are entitled to spy on you. Apple holds privacy and security as some of its core beliefs, so we'll have to wait and hear what the company says about the concerns Paul has raised. We've reached out to Apple for comment and will update this post with any updates. You can find the full article by Jeffry Paul here. FTC: We use income earning auto affiliate links. More.  Check out 9to5Mac on YouTube for more Apple news: |

| You are subscribed to email updates from "encrypted phone call app,the best encryption app,encrypted phone app iphone" - Google News. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

Comments

Post a Comment